Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) refers to a group of disorders affecting the peri-trochanteric space around the greater trochanter, leading to lateral hip pain due to damage or pathological changes in the surrounding structures. According to epidemiological studies, 14.3% of people over the age of 60 report frequent lateral hip pain, with a higher incidence in women than in men. The prevalence of unilateral GTPS in women and men is 8.5% and 6.6%, respectively, and the prevalence can be as high as 20.2% following orthopedic surgery.

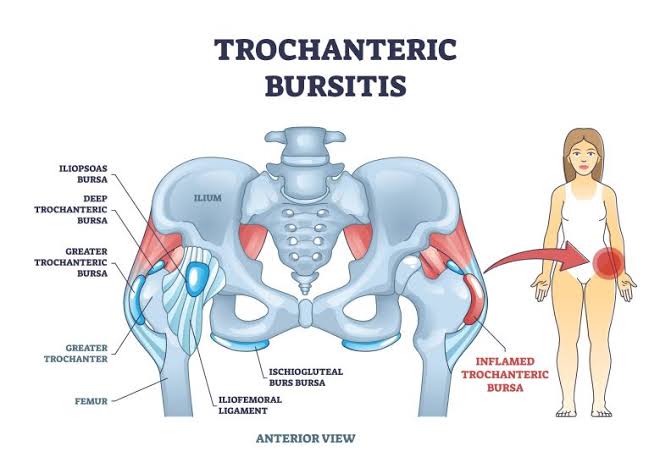

Anatomy of the Greater Trochanter

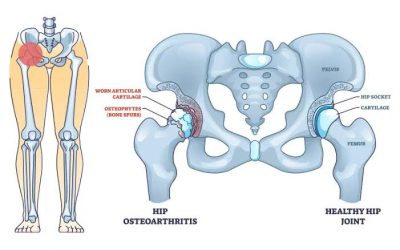

Anatomically, the greater trochanter is the lateral protrusion at the junction between the femoral neck and shaft and serves as an attachment point for several tendons. The gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae (TFL) muscles work together to abduct and internally rotate the hip joint. There is a space between the greater trochanter, TFL, gluteus maximus, and iliotibial band (ITB), known as the lateral hip space. The hip abductor muscles, including the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and TFL, form the foundational structures of this space, with the greater trochanter serving as their insertion point. The gluteus medius tendon that inserts on the anterolateral portion of the greater trochanter is thinner, which may explain its susceptibility to tears at this location. Studies also suggest that increased acetabular anteversion is associated with gluteal tendinopathy and trochanteric bursitis.

Pathogenesis of GTPS

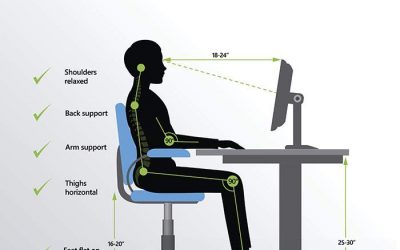

GTPS can arise from both intra-articular and extra-articular factors and may be primary or secondary to certain conditions. Contributing factors include aging, obesity, hip or knee arthritis, lower back pain, and biomechanical changes in the lower limbs, as well as muscle imbalances around the hip joint. Additionally, GTPS is associated with repetitive hip activities, local mechanical overload, improper training methods, and prolonged sitting. Common causes include trochanteric bursitis, abductor tendinopathy (gluteus medius and minimus tears), and iliotibial band friction syndrome, with multiple pathologies often coexisting.

Trochanteric bursitis, or inflammation of one or more trochanteric bursae, has traditionally been considered the primary cause of lateral hip pain. Bursae are fluid-filled sacs that lubricate the gluteal tendons and reduce friction during movement. The trochanteric bursa, located on the lateral side of the hip between the superficial hip abductor muscles and the deep ITB, is prone to inflammation due to friction between the tendons and the greater trochanter. This can result from repetitive microtrauma caused by excessive exercise, tendinopathy in the surrounding muscles, severe trauma (such as a fall), or idiopathic causes. In summary, trochanteric bursitis is caused by overuse or prolonged pressure on the greater trochanter.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with GTPS typically present with lateral hip pain and localized tenderness over the greater trochanter. The pain is often chronic and intermittent, affecting the hip, thigh, or buttock, and is exacerbated by prolonged sitting, stair climbing, vigorous activity, or lying on the affected side. The pain usually improves with rest, though night pain is common.

Physical Examination

Physical examination findings often include tenderness and percussion pain over the greater trochanter, as well as pain with hip rotation, abduction, or adduction. Specific tests include the FABER (Flexion, Abduction, External Rotation) test, Ober test, and resisted abduction test, which can help assess lateral hip pain. Among these, the single-leg stance (SLS), Trendelenburg sign, resisted external rotation, and hip lag sign are the most valuable for diagnosing lateral hip pain.

Imaging

X-ray: Radiography is the first-line imaging modality for patients with lateral hip pain. While X-rays help exclude intra-articular hip pathology such as bone tumors, proximal femoral metastases, trochanteric fractures, degenerative joint disease, femoroacetabular impingement, and hip dysplasia, they are not specific for diagnosing GTPS. X-rays may show irregularities or calcification of the greater trochanter’s surface, which are associated with abductor tendinopathy, but soft tissue imaging is limited.

Ultrasound: Ultrasound is a useful tool for diagnosing GTPS, particularly in detecting gluteal tendon tears with a sensitivity of 79%-100% and a positive predictive value of 95%-100%. Its advantages include low cost and the ability to perform dynamic assessments. During examination, the ultrasound probe can be used to palpate different tendon areas to localize the pain and guide diagnostic injections.

MRI: MRI is the gold standard for diagnosing GTPS, as it provides detailed assessment of muscle size, shape, gluteal tendinopathy, partial or complete tears, and fatty infiltration in the gluteal muscles.

Treatment of GTPS

The primary goals of treatment are to relieve pain, protect hip function, and improve quality of life. Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment, and surgery is only considered after 6-12 months of unsuccessful non-surgical treatment.

Conservative Treatment: Initial management includes rest, ice therapy, rehabilitation exercises, physical therapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Secondary options include corticosteroid injections into the hip bursa, shockwave therapy, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections. Research indicates that corticosteroid injections under ultrasound guidance provide effective short-term pain relief, especially when injected into the trochanteric bursa rather than the gluteus medius bursa. However, prolonged corticosteroid use may lead to tendon degeneration and rupture.

PRP is recommended in cases involving gluteus medius or minimus tendon involvement, as it promotes tissue healing through high concentrations of platelet-derived growth factors, reversing degenerative processes.

Surgical Treatment: Surgery is considered for refractory cases of GTPS when conservative treatment fails. Options include open or arthroscopic surgery to address issues with the ITB, trochanteric bursae, and gluteal tendons. Arthroscopic minimally invasive surgery is preferred, as it effectively repairs abductor tendons, reduces complications, and alleviates symptoms. In cases of ITB thickening or tension leading to friction, surgical release or lengthening may be performed, which has been shown to relieve pain and improve function.

In conclusion, GTPS is a common cause of lateral hip pain, and treatment should be tailored based on the patient’s symptoms, history, physical examination, and imaging results to improve pain, function, and quality of life. Further research is needed to clarify the underlying causes of GTPS and standardize treatment protocols. More randomized controlled trials are also required to evaluate conservative treatments like MTT and MET to develop clearer guidelines for diagnosis and management.